Book Review-How Good People Make Tough Choices: Resolving the Dilemmas of Ethical Living

Book Review-Emotional Intelligence

I read a lot of content on psychology. I love learning more about how people think. I am intrigued by different attempts to understand the human condition. However, I don’t find myself interested in studying the neurology of how the brain works. In Emotional Intelligence, I got both neurology and psychology in one convenient package. The neurology is of lesser practical value than the psychology is to me but it is nice to have support for some of the psychological ideas about how we believe the brain works through an understanding of the chemical and electrical interactions between different parts of the brain. So while I wasn’t looking for the neurology, it was very helpful in terms of validating the psychology.

Emotional Intelligence as a book has components which I can’t really process well. Certainly the neurology is a part of that, but more broadly, I think that there are some important lessons to learn that are woven into the text. Let me catch you up to speed on what emotional intelligence is, and then explore some of the nuances of the book.

Multiple Intelligences

Most of us have heard of the intelligence quotient (IQ). This measure was designed to assess how smart someone is, however, the way that it measures “smartness” is somewhat narrowly defined in the context of academic learning. It says nothing about how socially aware or in touch someone is. Further, IQ isn’t the strongest predictor of success over the long term. In contrast to IQ, the model of multiple intelligences was put forth by Howard Gardner as a model for depicting how people are gifted towards different aspects of the human experience. The idea is that individual areas of intelligence are only loosely connected to one another. Strength in one area doesn’t necessarily imply strength in another area. One particularly interesting intelligence that has emerged from Gardner’s thinking is Emotional Intelligence (EI). That is, how emotionally aware and connected a person is to themselves and to others.

Speaking as someone who has reviewed content for technical accuracy and clarity for dozens of years, I can tell you that statistical sampling doesn’t work when it comes to content. An author can be absolutely brilliant on one topic (say hard drives) and completely incompetent on another (say networking.) Overall they’re gifted. Individually they may – or may not – be in a given subject area. Because of this, it’s easy to resonate with me that we can have areas of strength and weaknesses in our intellect.

The Neurology of Love and War

You’re “keyed up.” You walk across the room unable to hear the voices around you because your heart is pounding out a lightning fast rhythm on your eardrums. As you reach the girl you so desperately want to ask out your mouth goes dry. Your brain is deep within a sympathetic arousal. Your brain has determined (incorrectly) that this moment is critical to your survival and if she says yes you’ll take flight and if she says no you’ll want to fight. Your body has prepared itself for battle. Your focus is so narrow you barely register the other people – even her best friend that she’s talking to when you walk up. In your head, she’s become the central threat of your world.

Six months from that moment, she’s said yes and you’ve been dating. This is when you’re both relaxing hand-in-hand, leg over leg, on the couch watching a movie, you’re likely experiencing a relaxation or parasympathetic arousal. That is, your body detects no danger and has lowered its guard. As a result you’re ready to work with your girlfriend on planning anything – even if it’s a wedding.

You’re seeing rather extreme examples of the neurology that happens in all of us every day. Sympathetic arousal quickens our pace, focuses us in on one or a few things, and gets us ready to fight or flee. This is the body’s normal response to stress and one that’s triggered by the amygdala. Conversely, a state of relaxation allows us to see more of the world. We’re able to see a broader view and accept views that may not be our own because we feel safe.

In Drive, Daniel Pink talks some about how we manage stress and how motivators narrow our focus. Fear works the same way. We ignore the extraneous to focus on the thing that we believe to be the most critical to our survival. When we’re in a sympathetic arousal state – for any reason – we’re going to be focused. That can be bad because the mechanics of our brain that manage stress weren’t designed for the kinds of stress we encounter today. Focus is important if you’re trying to run away from a lion on the plains of Africa – it’s less useful when you’re trying to determine which college to go to.

The Neural Shortcut

Fear flashes. In an instant you feel it. You saw something that you don’t even understand and now you’re afraid. How does that work? How can you be afraid before you even understand? In short, your amygdala. The part of your brain inherited from reptiles which is responsible for emotions and the fight-or-flight response. It’s raised the alarm. But how does that happen before you can even understand what it is that has been done?

Well, that comes from signal splitting and two different processes which are evaluating the signals as they’re coming in. The sensory input that you’re getting is routed to two different parts of your brain. The amygdala which is like the Paul Revere of the brain raising the signal that the British are coming. The frontal lobe also gets a copy. A more recent invention of neural biology, the frontal lobe is our rational consciousness. It carefully considers what we’re getting and does enhanced pattern matching to classify the information we’re getting. The frontal lobe doesn’t make many mistakes but in doing its careful analysis it tends to take longer than the amygdala.

From an evolutionary perspective having a few extra milliseconds to know about a threat can mean the difference between escaping a predator and being its next meal. So the amygdala makes a quick evaluation, determines that it saw a gun. It triggers the rest of the brain into alert. It causes the endocrine system to release chemicals and Paul Revere is on his ride through the body to mobilize every muscle. Sometime later – in the next few milliseconds – the frontal lobe makes its evaluation of the input and decides through longer evaluation that it’s a toy gun or it was just a kid’s finger playing a game of cops and robbers. The frontal lobe then explains “false alarm” and your brain – and body start to come down off of high alert.

The problem is that it’s too late to halt all of the effects. The chemicals that were released in those few milliseconds are already flowing through your body and while they have made you ready to move – to fight or to take flight – they’ve also altered your mood. The effect of that short flash can last hours. In Malcolm Gladwell’s book Blink, he speaks of the framing of input and how sometimes people make bad split second decisions because their perception is altered by the environment. Gary Klein in Sources of Power goes to great lengths to explore how people make decisions – and in the latter half of the book describes how the context of events often times do change the decisions.

Daniel Kahneman speaks more directly about this in Thinking, Fast and Slow. He speaks about how we have a quick mind that works all the time, silently taking care of things until it discovers it doesn’t know how to process something, when it then engages a secondary and slower system. The trick is that the automatic, everyday fast system doesn’t always engage the secondary processes when it should. We can say the same thing about our emotions, sometimes we’re not aware of the need for some rational counter balance to our feelings.

Emotional Hijacking and Cognitive Incapacitation

What about when the frontal lobes can’t reign your emotions back in? At some level you’re aware that someone didn’t intend to make you angry. They’re not really a threat. They can’t really harm you. Despite this, there’s a feeling that you just can’t shake and more importantly, you’re doing things that you know are ultimately very destructive to you, to others, and to your relationships. Welcome to emotional hijacking. You quite literally don’t have the capacity for reason. Temporary insanity defenses sound insane – except that from a neurological perspective there’s support for this happening. The amygdala takes over control and any of the expectations of a civil society are off the table.

The normal circuitry in the frontal lobe for telling the rest of the brain and body that the amygdala is “crying wolf” are shut down. The frontal lobe simply doesn’t have the ability to regain control. Eventually the amygdala won’t be able to sustain control and will give up – however, that can be hours away.

There’s a different kind of problem that sometimes occurs as well. It’s not about a quick emotional hijacking based a single event. It’s a slow, building level of saturation in the system from which it becomes impossible to think. Consider the quote from Ghost Busters — “I’m terrified beyond the capacity for rational thought” – Dr. Egon Spengler. The line is funny because it’s not an emotional hijacking – the character is aware of his feelings but he’s not wrestling control from rational thought. Instead the ability for rational thought is suppressed due to overload – due to flooding. Rational thought is slower and too much input and memories have overwhelmed the ability to process.

So what do we do about it? Earlier in my career I worked for Woods Industries and one of the product lines was surge suppressors. They work based off of something called a metal-oxide varistor (MOV). A MOV has high resistance at low voltages and low resistance at high voltages. So when the voltage is high (like during a surge) the resistance is reduced and current can flow more freely. What happens is that the MOV shunts the power to ground, suppressing the surge. This works great. However in the process of shunting the power sometimes the MOVs build up damage. The damage comes in the form of a pathway inside the MOV which doesn’t work the right way. Bad patterns develop which make the MOV less effective.

The key is to develop positive patterns that create easier pathways to follow when there’s a chance of emotional hijacking or cognitive incapacitation. In the case of hijacking, it might be a habit of counting to ten before taking an action – basically breaking the hold of the amygdala by introducing a short break. Addressing cognitive incapacitation might require a longer period of time – and an agreement to walk away from the conversation (or confrontation) for a while so you have time to process everything that is coming at you and everything that you’re feeling.

The Tale of Two Minds: How We Do Emotional Processing

It’s widely believed that talking about your anger makes it better. It’s called cathartic. The only problem with this is that it’s not true. There seems to be no therapeutic benefit from talking about your anger. In fact, talking about it in the wrong way can actually reinforce and intensify the feelings and make them more difficult to deal with. If you think about what’s making you angry – if you focus on it, you reinforce the anger – rather than releasing the energy from it. A more effective strategy is to tear the emotion apart and figure out what is causing it.

I once listened to the audio version of the book Destructive Emotions which was a dialog with the Dalai Lama. In that book there was a comment that in eastern philosophy “anger is disappointment directed.” That one statement has been, perhaps, one of the most valuable things I’ve ever heard. It allows me to ask the question when I get angry… what am I disappointed by? This allows me to try to process my emotions and figure out what’s behind them. Fear is similar. Fear is that we feel threatened. A good question is: how do I feel threatened? Once I get that answer, I can ask the “Why?” question.

This activity is the frontal lobe processing the emotions that were triggered by the amygdala. Processing emotions can be very healthy as it allows you to learn how to self-manage your emotions – once you’re aware of them.

The Voice inside Your Head (Cognitive Therapy)

“You’re not good enough.” “You’ll never be fast enough.” “You’re not as smart as your sister.” “You’re amazing.” “You’re special.” “You bring smiles to other people’s faces.” Some version of one of these is playing in your head from time-to-time. It’s an internal tape. It’s a sort of background noise to the way that you think. These little voices keep talking to you over and over and over again. Eventually, whatever those voices say is what you’re going to believe.

One of the most effective therapies developed has been cognitive behavior therapy. That is the process of changing the voices in your head from relatively negative voices to more positive voices. The voices that we start out with are ones which are echoes from what our parents, friends, and our relatives have said. They make up our core beliefs about ourselves and while our core beliefs about ourselves can’t be changed directly, these voices can be changed.

This is particularly true of how we see emotion. If we believe that our anger is justified then our internal voice may reinforce it. If, however, we view the way that we’ve acted as a result of our anger as bad we may choose different ways to express our anger next time. A voice that says I’m a good person but that I’ve chosen some bad approaches will be more effective than I’m a bad person and I’m doing bad things.

It turns out that there’s a difference between guilt – admitting I’ve done something wrong – and shame – believing that I’m inherently bad. A voice that tells me I’m a good person who made a bad choice. By being conscious of the voice that’s playing inside our heads and shaping it in more healthy ways, we can shift our feelings by creating better emotional reactions.

Of Self and Social (The Heart of EI)

What is emotional intelligence? According to Goleman, there are four keys to emotional intelligence:

- Self-Awareness – This is an awareness of what you’re feeling (and thinking). It’s about knowing you’re grumpy, angry, hurt, or tired. You can’t very well be in touch with yourself if you can’t describe your feelings.

- Self-Management – The first step may be awareness that you’re angry – but what if the anger isn’t appropriate or it isn’t appropriate to express? Self-Management is a set of skills that allow you to regulate or manage your feelings.

- Social Awareness – Knowing how you feel may be essential, but in relationships with others the ability to detect their emotional state is critical. It’s the foundation of empathy and the ability to be in relationships with others.

- Relationship Management – Being able to be in relationships is the pinnacle of emotional intelligence. Knowing how to relate to others at a deep level enriches lives.

Characteristics of Character (Enthusiasm, Persistence, Hope, Unflappable)

What makes someone successful in life? I’m not just saying successful in terms of being financially wealthy but rather successful in a more holistic view of loving their life. As it turns out some of the most telling factors for how successful someone will be in life aren’t about IQ. They’re more about Emotional Intelligence. It turns out your ability to monitor your feelings, distract yourself, manage your responses, read others’ emotions and feelings, and ultimately manage your relationship with others is more important than any other factor in terms of your long term success.

A famous study most often referred to as the marshmallow experiment tested delayed gratification (which is essential for self-management and relationship management) by offering kids one marshmallow now – or two if they waited. This isn’t interesting in itself. What’s interesting is that those preschoolers who were able to delay gratification and get the two marshmallows showed significantly more successful measures of life. In other words, something as simple as whether you can delay your own gratification has a substantial impact on your long term success in life.

However, delayed gratification isn’t everything. Persistence has its place. Consider Lincoln. Our most beloved president had a string of political losses before becoming president. His wife was widely reported to be a very difficult woman to live with. Yet, through set-back after set-back he managed to move forward in his life and lead the country through one of its darkest hours. Consider Einstein. Most folks believe that he was a brilliant man – and he was – but what they don’t realize is that he struggled in school. He often spoke of the fact that he wasn’t smarter than others – just more persistent. If persistence makes folks like Lincoln and Einstein … sign me up.

What is perseverance when you have no enthusiasm or passion for what you’re doing? You may keep moving forward but it will grind you down. It will wear at you. We’ve all seen the army of bitter people who continue to struggle to move forward but they aren’t enjoying their world. They’re simply surviving. There’s something to be said for bringing enthusiasm to each new challenge. Consider Edison. He was creating things that didn’t exist before. While we may be mystified by LED and compact florescent bulbs, consider a time when even the incandescent bulbs didn’t exist. Candles and lamps provided light at night. Edison reportedly had a thousand failures at creating a light bulb, however, he refused to count them as failures. Instead he chose to say that he had discovered a thousand ways NOT to make a light bulb. That’s enthusiasm.

Oprah liked the book The Secret and drew heat for it. The central premise of the book (as I understand it, having not read it) is that you attract what you think about. If you think positive thoughts positive things will flow into your life. I don’t go this far in terms of my beliefs, however, I will say that looking for the positive in every situation – finding a way to cultivate your hope for a better future is important. As I mentioned in my review of Who Am I?, Viktor Frankl, a concentration camp detainee, observed that folks who had a meaning for their life were the ones that survived – hope is that sort of meaning. I hope (or believe) that my suffering will serve others – and in that I can survive even the most miserable circumstances. Hope is a key characteristic of a happy life.

Hope waxes and wanes in each of us, however, there is a characteristic of unflappability – an inability for people to be disturbed by what is happening around them. Unflappability can actually be caused by two different things. One is an inability to process your environment emotionally, which would be bad. However, there’s another side. That side is the mastery of the ability to be aware of and manage your emotions so well that seemingly nothing fazes you. This can be very healthy.

The Great Paradox: You Must Feel Safe to Become Vulnerable

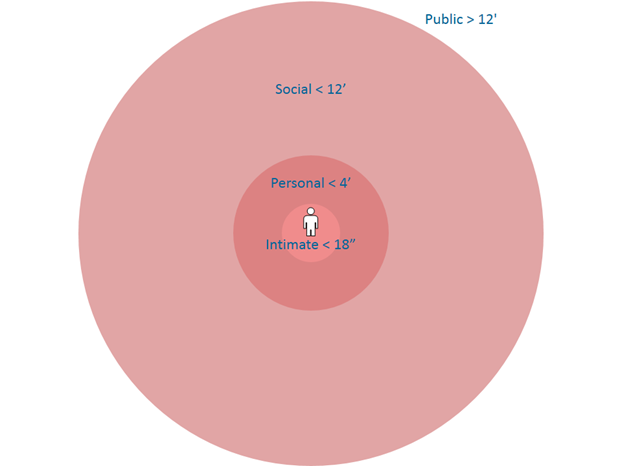

I learned more about how trust is reflexive – that is, the more you trust, the more others trust you – from Trust & Betrayal in the Workplace and Building Trust: In Business, Politics, Relationships and Life. There’s a sort of inherent elegance in this. There’s almost an innate understanding that you trust those who trust you. However, there are parts of the human experience in which the way to get trust is counter intuitive. Trust is allowing yourself to be vulnerable – vulnerable to a failure in another person.

However, someone else being vulnerable to you isn’t going to be enough for you to be vulnerable. You have to feel safe. Certainly trusting the other person is a good start, however, you have to feel safe in general. The trick is that being safe and feeling safe aren’t the same thing. Many people have an anxiety when flying on a commercial plane. Of course, flying in a commercial plane is substantially safer – statistically speaking – than driving your car to the airport to get on the plane. This doesn’t stop the anxiety.

Conversely, you probably feel very comfortable in your own home. However, in-home accidents are a leading cause of death. So while you should feel safer in an airplane and less safe at home, the opposite is true. It’s an odd thing to realize that you have to feel safe to allow yourself to be vulnerable.

Finding Emotional Intelligence

No one book will dramatically change your life and improve your emotional intelligence overnight, however, if you’re looking for a way to get in better touch with your emotions, to control your responses, to understand others, and to be in relationships with others; Emotional Intelligence is a great place to start.