Book Review-Collaborative Intelligence: Using Teams to Solve Hard Problems

Like many people, I enjoy action movies where there are terrorists trying to wreck our world and the lone hero – or hero team – that are standing in the breach between the terrorists and our way of life. However, I’ve never really given much thought to what it would be like to be in an intelligence community. I can quickly spot the flaws in a plot line but I’ve never given much thought to what would have to happen to prevent terrorists. However, I found the view of intelligence communities, provided through Collaborative Intelligence very intriguing. I didn’t pick the book up to learn about the intelligence community – I picked the book up to learn about team dynamics – but it was interesting.

Many places where you start to study about team effectiveness you’ll find references to Richard Hackman’s work including articles and papers. Collaborative Intelligence is his latest (and sadly his last work.) It lays out six conditions to increase the potential for team effectiveness and three criteria for measuring the performance of teams. The work lives outside the bounds of the traditional cause and effect popular management books of the day. Hackman doesn’t seek to tell you one way to be successful. In that way it’s like The Heretic’s Guide to Best Practices. Instead, Collaborative Intelligence is about the things that can make it more likely for teamwork to work – and things that work against it.

Three Criteria

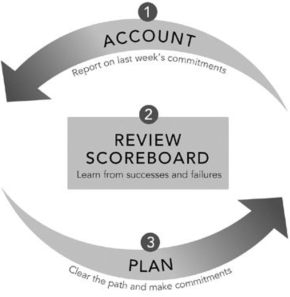

Hackman ultimately was interested in making teams more effective but more effective by what measurement? It’s possible to be focused on only the results but as I discussed in my reviews of The Fifth Discipline and The Four Disciplines of Execution, this isn’t really enough. You have to look earlier into the process – and later in the process. Hackman uses three criteria for team performance:

| Criteria | Indicator Type |

| Productive Output | Lagging |

| Social Processes | Leading |

| Learning / Growth | Far-Leading |

Hackman also discusses three team processes that I believe fall into the category of sustainability which I’ll cover first, before covering Hackman’s three criteria.

Sustainability

In agile development there’s a concept of a sustainable pace. In a market dominated by hero development where a lone programmer stocks up on Mountain Dew and Doritos and spends a few days without sleep, coding something magnificent, there’s a palpable awareness of how things must be sustainable. You can’t continue to drive developers above a sustainable pace any more than you can make a horse run continuously. For instance, the Pony Express swapped out horses after relatively short distances because an individual horse couldn’t sustain the high speed that they were asking of them.

Hackman measured three key team processes to observe the sustainability of the team:

- Amount of Effort

- Team Choices

- Level of Knowledge and Skill

Hackman was measuring the same sustainability metric by looking at the amount of effort that the team was putting in order to get their output. It’s certainly possible – and productive – to burst activity towards the goal but those bursts have to be paid for at some point.

Team choices are about the social dynamics and making sure that the team is collaborating to produce strategies for getting the work done instead of allowing one or a few members to dominate the approaches. If approaches are thoroughly thought out by the team and negotiated to agreement (not just acceptance – see The Science of Trust and How to be an Adult in Relationships for more) then the team is likely to be able to continue to operate for some time effectively. If one person or a small group are dominating the approach decisions then eventually they’ll run out of good ideas or the rest of the team will revolt – or both.

Finally, you can only get lucky for so long. If you’re working in uncharted waters where there the team has no knowledge or skill you can “get lucky” with some early successes, however, eventually the team will make a mistake because they’ve never done something. Knowing how much knowledge and skill is being applied to the problem at hand helps you to understand the risk of a small failure.

Together these measurements allow you to see how long the team can sustain its productive output.

Productive Output

At some level every team gets measured on its results so it is no surprise that you would measure the output of the team. However, as mentioned in The Four Disciplines of Execution, output is necessarily lagging. (Also see Thinking in Systems for delay.) To be able to intervene and make changes you need leading indicators, like the social processes in use.

Social Processes

Anyone who was a part of a large family has seen sibling rivalry and has seen the sarcastic “picking” at one another that sometimes happens in a family. Some of us have seen a mostly different experience where siblings go out of their way to support one another. Whether it’s complimenting an accomplishment, encouraging around a disappointing setback, or simply listening to the world of the sibling without comment, there’s a more supportive social construct that can also develop.

Hackman measured how the social processes of the team were working. They were looking for how the team was building each other up, not tearing each other down. When a team works to support individual member’s weaknesses — we all have them — rather than attack them, the team is more effective. The more that a team can develop an open, honest, and supporting environment the more likely it is that the team will be successful in creating it’s deliverable – and helping each of the individual members to grow.

Hackman knew that overtime the ability of the team to support and accept each other’s weaknesses would improve productive output – and perhaps even spur individual and team learning.

Learning and Growth

Measured in the long term the current project doesn’t matter. The current team effectiveness will be a faded memory. However, what will really resound is the velocity with which the organization moves. The velocity of the organization is driven by the ability for its teams to get things done and that means that teams need to get more effective over time – over the long time horizon. That is done by ensuring that the team dynamics foster the growth of individuals both in their ability to work in a team as well as their individual skills.

One of the great things about Ford’s assembly line was that he could leverage unskilled workers because the requisite skill to work on the line was low. One of the worst things about the assembly line was that the assembly line didn’t encourage, support, or to some extent even allow, workers to grow their skill level. While we still use assembly lines in the production of some things, the way that they’re executed are much different. They take advantage of lean manufacturing thinking and cellular manufacturing to create an opportunity for the individual workers to become more skilled – and there by create the opportunity for success.

Knowing that we want to improve outcomes, improve our interactions, and improve our people, we need to explore the conditions that lead to these outcomes.

Six Conditions

What makes some teams very effective and some completely ineffective – or perhaps even capable of moving an organization backwards? There’s no one answer to that question. Certainly individual performance and competency impact the capabilities of the team, however, some “dream team” collection of players work spectacularly and some fail miserably. Certainly there’s more to a team than the sum of its parts. That’s the core of the six conditions which are:

- Real Team

- Compelling Purpose

- Right People

- Clear Norms

- Supportive Context

- Competent Coaching

Let’s look at each condition in more detail.

Real Team

Sometimes organizations create groups of people and give them a name like “Team Quality.” However, giving a group of people a name doesn’t make them a team. Instead teams are “a bounded set of people who work together over some period of time to accomplish a common task”. Hackman describes several kinds of collaboration. The types of collaboration he discusses are:

- Community of Interest – A loose collection of individuals that share a common interest. They have no common task, timeline, nor membership.

- Community of Practice – A loose collection of individuals that are leveraging the collaboration to accomplish their own organizational goals. They too, don’t share a common task, timeline, nor is there typically a clear membership.

- Emergent Collaboration – Sometimes individuals are assigned similar responsibilities inside of different teams or organizations. These teams share information among the group for the betterment of all. IT security groups that share the latest information about current threats, schemes, and tools are an example of emergent collaboration.

- Coacting Group – Commonly a collection of individuals performing similar – but not interrelated tasks – are called teams but are instead coacting groups. They are not working together to accomplish a common task. They’re working individually to accomplish the same task.

- Distributed Team – A distributed team isn’tt located together and therefore must rely upon technology and travel to stay coordinated but they do generally have a clear membership and do share a common goal. Distributed teams have coordination challenges. Many of these challenges are described, in agile development and knowledge management literature.

- Project Team / Task Force – The project team meets the definitions of a real team but tends to have a relatively short life. The team is formed the mission is accomplished and the team is disbanded.

- Semi-Permanent Work Team – Similar to a project team but more typically aligned departmentally a semi-permanent work team focus on operational work – or a stream of projects – and works together towards those goals with not specific end to the work.

The last three types of collaboration are considered – by Hackman – to be real teams.

Compelling Purpose

Strangely many teams don’t know their real purpose. They get wrapped up in the operational details of the work to be done and never get focused on why they’re there. Collaborative Intelligence speaks of exercises where a red team (terrorists) are attempting to attack while a blue team (good guys) are attempting to thwart the red team. A great deal of time is spent talking about why the red team has a set of serious advantages from a teamwork perspective. Not the least of which is that the purpose for the red team is quickly formed from a simple offensive goal, whereas the blue team frequently struggles to convert a generic “defend” goal into a set of meaningful actions.

Red teams are given the purpose of disrupting and often start by the members throwing out their skills that might be helpful to the group while blue teams often throw out their positions in their organizations. Red teams move on to forming a specific approach to accomplish their goal while blue teams flounder trying to find their purpose.

While the two teams have a clearly stated goal the red team has the ability to convert their generic purpose into a specific set of actions. Often this goal – where the approach to accomplishing the goal is specified by them – represents some sort of a stretch where they’ll need to bring in skills and knowledge from others to accomplish it. This maps neatly into Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s work on Finding Flow. They’re able to moderate their difficulty level to a point where they’re most effective.

The real “red teams” are also able to frame their objectives in terms of a broader mission. In other words, their work is seen as consequential to their greater purpose.

The blue team may be able to “protect” but this isn’t typically specific enough to achieve the goal of a specific set of actions for thwarting the red team. While their work is consequential to protecting their way of life, the difficulty in getting clear about the exact approach can be very disruptive to performance.

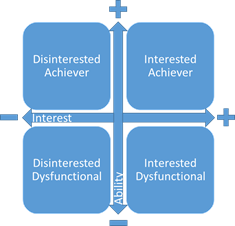

Right People

Jim Collins in Good to Great starts off with getting the right people assembled. His metaphor is that you have to get the right people on the bus first. Hackman agrees that having the right people in the right positions is critical to team success. Specifically he was concerned whether or not team members had the right skills – or aptitudes. In his research he found that ensuring that a team had all of the required skills – they knew what to do – or the right aptitudes – they could learn what to do — was an important first step. The next step was to design the team so that the skills of the individual team members can be leveraged. Teams with the right skills and the right design were nearly 40 times as powerful as teams without the required skills and design.

While Hackman suggests that direct skills are best for team design he also indicates through his research that aptitude for the subject area or even in some cases general intelligence is effective at creating well designed teams. This is particularly true when the team is coupled with good coaching around the areas where they don’t have core skills. (See condition number six).

Hackman is equally clear that having the right number and mix of people is essential. It’s important to support the team with resources (see condition five) but not to over provide them with resources so that they will blindly accept a sub-optimal strategy. This applies to people resources as well as material resources. Keeping the team slightly under resourced leads to more productive teams.

Finally, Hackman admits that the data is that one bad apple can spoil the bunch. An entire team can become derailed with a single bad person. So it’s often better to get rid of one person who is disruptive to teamwork – even if that person has key skills that are perceived as necessary because it’s possible that the rest of the team can’t be effective with a single bad person in place.

Clear Norms

Defining normal is a power force. One of the barriers to adoption of a new technology or approach is not having norms. Establishing the rules of behavior for teams can be important and powerful as well as helping the team organize into what is – and isn’t acceptable. In fact, Hackman found that establishing clear norms was more strongly associated with team effectiveness than any other factor. There are two key factors in how powerful the norms will be.

The first factor in the power of the norm is the vigor with which the group will defend the norm. Some things are defined as normal behavior but for which there aren’t clear, consistent consequences for not following. For instance, there may be a norm that you wash your own coffee cups in the break room but since there’s a receptionist who will wash them if you don’t there’s little vigor of enforcement.

The second factor is the level of agreement on what the norm should be. Crystalized norms, those with which there is nearly complete agreement, are different than norms of conduct that most people agree to – but not everyone. The lack of crystalized norms reduces enforcement but also reduces the ability to develop a set of universal expectations about what is and isn’t acceptable.

Don’t let the simplicity of establishing norms fool you. They are sometimes difficult to create. One way to speed the process is to borrow norms from other groups or situations and either get buy-in or simply decree that it’s the normal. As long as no one is willing to stand against the proposed normal, it can quickly be adopted by the group.

Supportive Context

A friend once said – to his boss – that his mission on the helpdesk was like being parachuted in behind enemy lines with only a spoon. Needless to say he didn’t feel like he was being well supported. It’s not surprising that he and his team struggled to be effective because they found themselves spending most of their time working around the things they did not have. Hackman’s work identified that the supportive context of the organization made a big difference in the ability for the team to be effective. Specifically there are four key aspects of supportive context:

- Access to the information a team needs to accomplish its work.

- The availability of educational and technical resources to supplement members’ own knowledge and skill.

- Ample material resources for use in carrying out the team’s work.

- External recognition and reinforcement of excellent team performance.

The presence of these four things represent a supportive context under which the team is more likely to succeed. As mentioned earlier, having what a team needs isn’t about over supplying the team, however, it is about giving them what’s minimally necessary to be successful. One of the specific things that teams need are competent coaching.

Competent Coaching

Most of the research on coaching has been evaluated at an individual level. Did the coaching work for a specific person on the team. Most of the individual coaching is done in the vacuum of an off-site workshop where folks are given a synthetic scenario to solve – or are being taught that their team members will catch them when they fall. While these exercises get good marks in post-event feedback studies, it’s not been conclusively proven that these sorts of interventions are successful at driving a chance in outcomes.

The first part of competent coaching is simply finding the right coach with the right experiences to be able to help. Coaching is difficult to measure effectiveness before starting and because each situation is different it’s difficult to see if a coach will be effective for your situation. (See wicked problems in Dialogue Mapping and The Heretic’s Guide to Best Practices.) Strangely Hackman discovered that better coaching was less interactions. Experienced coaches waited longer to provide feedback to give themselves more time to see the problem and to consider a response. They seemed to inherently know that there’s a limit to how much coaching an individual can take in a given time.

This runs counter to the idea that the sooner you make a correction through coaching the less rework and redirection must be done. This is, of course, true, however, the other factors in the system are more important than the redirection. (See Thinking in Systems) In fact, Hackman found that different kinds of interventions were better at different times. So not only was it good to reflect on the situation before providing coaching but sometimes the type of coaching changed based on where the team was in its lifecycle.

When starting a project, teams are most responsive to motivational interventions. They want to be “fired up” about the shared challenge that they’re getting. However, engaging the team in discussions about the alternative ways of going about the work – picking a process to follow – are ineffective. It isn’t until the midpoint of the team’s life where they’re willing and able to evaluate their processes and refine them. It’s then that the consultative approach of optimization and reflection is effective.

The final part of the lifecycle is the near end or post end when things like after action reviews (See The New Edge in Knowledge Management and Lost Knowledge for the importance of after action reviews.) Most teams struggle to do after action reviews because they see little direct value. However, Hackman measured teams effectiveness based on how the teams became more effective both individually and as a team as a part of the process and so the ability to capture what the team learned is important to informing the next teams.

Beyond the timing and quality of the coaching, there are even dimensions of how the training is conducted that are important to whether the training will be effective. The first is whether the coaching is focused on individuals or teams.

Individual coaching may be effective at improving individual skills and in some cases individual coaching on how to participate in a team may be appropriate (see Right People above). However, coaching targeted at the team can be much more effective.

Another dimension of the effectiveness of coaching is whether the coaching is focused on the process of teamwork – or on the task at hand. The assumption is that working on the harmony of the team – the process of teamwork – is what causes teams to be effective. However, it may be that effective teams become harmonious – that we’re reading the causal relationship in reverse. It appears that the goal of a team shouldn’t be harmony – because there are numerous successful teams that aren’t harmonious – but instead the focus should be on respect. If you respect and trust one another the team is more likely to be able to avoid traps like “groupthink.” (See my post on Trust=>Vulnerability=>Intimacy for more on trust.)

The research indicates that coaching on the actual work that the team is doing is more effective than process coaching. It seems that helping the teams solve their problems and better understanding the challenges of their space is more effective at helping them than coaching them how to operate more effectively. Hackman’s research showed that no amount of team structuring, or process coaching was effective at improving performance of a team when there weren’t the people who had the requisite skills or the ability to get them. In fact, process coaching when the team didn’t have fundamental skills just reduced their performance.

60-30-10 – Setup, Startup, and Operation

Hackman asserts that sixty percent of a team’s effectiveness is in the setup, another thirty percent is in the startup of the group, and only the remaining ten percent can be accounted for by tweaking various operational parameters after the team is up and running.

The setup, in Hackman’s view, is the team’s purpose, composition, and design. That is what the team is tasked to do, the team members selected, and the roles that the members are expected to perform.

Certainly there are others that would agree that setting the right goal is important. We saw Loyola implore the Jesuits to focus on the right outcome not the trivial details in Heroic Leadership. Covey was clear about beginning with the end in mind in The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People.

The composition – getting the right people – is something Jim Collins emphasized in Good to Great. It’s also the focus of books like Who: The A Method for Hiring. There’s a great deal of research on how impactful getting the right hires for an organization can be.

Judging simply by the sheer number of management books available all aimed at getting the right skills into the right roles there’s little doubt that there’s a belief that the design of the team – what they’re expected to do – is important as well.

The next step in Hackman’s model is the startup or launching of the team. One component of launching is the communication of the purpose of the team. Something that no doubt Patrick Lencioni would approve of, given the focus on clarity in The Advantage. Similarly John Kotter’s model for change focuses on the need to build a coalition and communicating the change as discussed in Leading Change and The Heart of Change.

Similarly how a team is introduced to one another is important. By introducing skills – rather than introducing positions or groups – the team can focused on how they work together not what stereotypes they have of the group from which the member came.

Finally, Hackman discusses how facilitating – coaching – can be effective. However, he cautions, as mentioned above, that the right kind of coaching should happen that the appropriate time in the team’s lifecycle.

Cost and Utility of Information

One rather accidental observation that Hackman raises repeatedly is the bias for intelligence groups to treat information that is difficult to obtain as more valuable than information that is readily available from public sources. This reminds me of an admonishment from a CEO when I was doing product management work years ago to not do “cost+” pricing. That is that the price that we can obtain from the market for a product doesn’t have anything to do with the actual cost of manufacturing. We should focus on the utility of the product and what the market is willing to bare – instead of what it costs us. Douglas Hubbard in How to Measure Anything also shares that just because something is harder to get doesn’t make it better – in fact, it often makes it less good.

The point, however, isn’t that we shouldn’t judge the value of information based on its cost – the point is that we as humans often have trouble separating the effort that we spent to get something and the value it delivers. Luckily I have a reasonably good reminder. I have desks that I literally built out of door jamb, file cabinets and pieces of tempered glass. The desks weren’t expensive – but they’re incredibly effective at keeping my stuff off the floor. It’s my visual reminder that just because something is more expensive doesn’t make it better.

Collaboration in the End

Good collaboration – good teams – in the end are about the organization of appropriate individual team member skills to accomplish the goal and for the development of everyone involved. Good collaboration has each member supporting other member’s weaknesses without complaining or condemnation. Team members build each other up rather than tearing them down. If you want to figure out how to create these kinds of teams, read Collaborative Intelligence.